Calvin started going to the diner as an escape. He wanted to avoid church, but his parents made him promise to acknowledge God, His presence, at least once a week. There was a youth group with few youths—Calvin had gone and then said he would keep going; by then, he’d begun his detours to the diner. When his parents asked, it was easy to lie.

A diner for two hours was better than the youth group, better than Sunday services. A diner by himself was better than trying to understand people who didn’t sign.

The services were heavy on the hymns, heavier on the organ. The handful of times Calvin had gone, the organ came through his hearing aids like a bellowing from underground.

“We are blessed to have good fortune in our lives,” his father intoned to him, the night he moved here, right after he had graduated from his Deaf school. They were eating dinner, his father pinning Calvin under his gaze. “It would be good for you to see that, before college.”

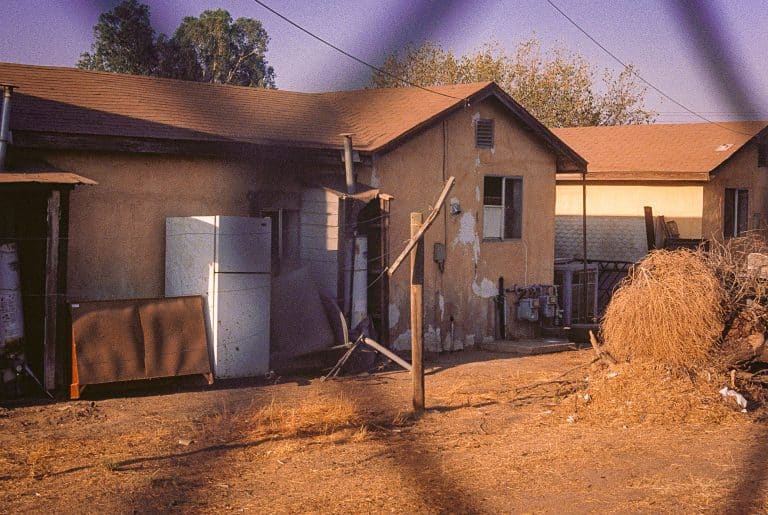

Before college. Before Gallaudet—before Calvin could go to the East Coast to find a new family, a new community, at another Deaf school—there was going to be Los Suelos. His father had found a job as head preacher in this dusty little Central Valley town. The Kesher family had found roots here.

The diner started as an escape. It became a place more familiar than home. The waitresses gave him free cups of coffee and discounts on food. He learned who gossiped in the diner and who didn’t. He learned who to avoid. The Belowdowners always invited him to movies, scrawling the questions on napkins; he stared directly at them and shook his head. He sat himself in every booth and learned where to look, who to watch, so he could learn this town, this strange liminal space between one home and the next.

Calvin had never stayed in a town that had a slaughterhouse. He’d never stayed in a town where there buzzed whispers, as his mother told him, about cows that could talk.

As the days wore on, Calvin dreaded going home because of what awaited him there. The diner was open twenty-four-seven and he could have stayed. He’d learned the little nooks in the kitchen and bathroom that remained unchecked. He only went home out of respect for his parents—and fear of gossip getting back to them.

Still, he had to take off his hearing aids before he crossed the threshold. Otherwise, his chest would spasm, in either sympathy or revulsion.

The sound of his father’s coughing filled the house, a presence that seemed to fill up every possible inch of space. It was audible to Calvin even as he took his hearing aids out, even as he laid himself down to sleep.

“Will you take this to your father?” his mother always asked, minutes after he entered. “Will you take this chicken broth to him?

“Will you take this cup of water to him?

“Will you give this cough medicine to him?

“Will you give this antibiotic to him? This herbal remedy?”

Calvin only agreed because his mother’s face looked like it would splinter and reveal something inhuman if he didn’t.

His father’s bedroom—because his mother was sleeping on the couch, because it was the only way she could sleep—was a yawn of darkness. The windows were blacked out. Calvin put his hand out and one foot in front of the other until he came to the closet’s doorknobs. From there, it was two steps to the right and then he was right in front of the bedside table, right next to his father.

Calvin had to press his lips together, firmly, every time he put something down on the bedside table. The stench of shit and vomit was overpowering. He swore, even without wearing his hearing aids, that he could hear something rattle, wet and heavy, in his father’s chest.

After he closed the door behind him, Calvin always felt as if he’d crawled out of some dark mouth that, any second, could have closed on him.

One day, late July sun beaming down, Dr. Knightley sat down in Calvin’s booth, opposite him. He smiled, his gaze steady on Calvin.

Dr. Knightley had asked to sit with him, the waitress wrote on her notepad—did Calvin mind, eating with someone? He shook his head. He put his hearing aid in. The diner then buzzed with activity.

“How’s your father?” Dr. Knightley asked.

“The same,” Calvin replied, his voice raspy from lack of use. He hadn’t used it since June. “Coughing out of his mind.”

“Has his throat come out yet?” Dr. Knightley asked. Calvin laughed, a one-note sound hard with forced amusement, then he saw how serious Dr. Knightley’s face was. He shook his head.

“Does he know we can help him?” Dr. Knightley asked.

Calvin shook his head again. “My father is wary of medicine. He prefers faith.”

“But medicine has an answer for most things. He should have come to us when his coughing started,” Dr. Knightley said. “Tell him to hold on. He may be stronger than the preachers we’ve had before. Tell him to stay above ground. There’s hope, even in the foul darkness of his bedroom.”

Calvin blinked. “How do you know his bedroom is dark?”

Dr. Knightley smiled. After he finished his eggs Benedict, Calvin let Dr. Knightley take his hand, as though he were a child going through a haunted house, and they went to the medical clinic. Dr. Knightley kept a grip on Calvin as they went through the waiting room, down the hallway, past the examination rooms.

In an office, there was a corkboard. It featured a map of Los Suelos, punctured with little pins. There were old photographs, mostly blurry; some seemed to capture obscure shapes passing through the static, flat landscape. There were newer photographs of cadavers, of body parts and openings, each part and body and face gray with death. Dr. Alan Knightley had included handwritten items, notecards, notebook pages, and medical reports. All pinned to the corkboard.

There were pictures of throats, labeled. There were pictures of lungs, dark and leathery like a bat’s wings.

Dr. Knightley stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Calvin. He had let go of Calvin’s hand some time ago and Calvin wished he could pick up Knightley’s hand again. He wanted Knightley to guide him to an answer, or a haven.

“I don’t know what’s causing these deaths,” Dr. Knightley said. His face looked sallow and washed out under fluorescents. “I only know how they begin. They always start off coughing, like something inside their bodies is fighting to get out.”

“What else happens?”

“Pleural effusions. Bronchitis. Pneumonia. They cough until they vomit. They cough up blood. Sometimes they speak foreign languages.”

“Foreign languages? Like Spanish?”

“Not Spanish. It’s nothing we know. But it always ends the same way. Their voice boxes collapse, and then there’s just this awful sound. They try to speak without sound. They try to cry. All that comes out is air. It’s silence after that.”

“When do they die?”

“The silence becomes too much. They fight and fight to speak into the silence, and they can’t. And sooner or later, all they can do is dig.”

“Dig?”

“They find a new kind of voice inside them. A new kind of calling. Not above, not towards Heaven, but below.”

Calvin carried Dr. Knightley’s words inside him as he went back to the diner. The sun was low in the sky now, beams long and orange over dirt. It looked like the world was on fire, and it made Calvin want to be swallowed by flame.

In the diner, the waitresses saw him and started. One of them rushed towards him and hugged him. Her smell mushroomed around him, starchy and crisp. Her apron crinkled against his thighs.

“I’m so sorry,” she said when she let go of him. “We’ll cook you anything you want, free of charge, anytime you need.”

Calvin read her lips and shook his head. Confusion made his head swim, like the fire had already ignited in his head. Below the confusion was dread, as if he’d suddenly plunged into water after breaking ice. Maybe silence was closer than he thought.

“What happened?” he asked. “I’ve been with the doctor.”

The waitresses ushered him to a booth. The cook made him French toast, and sausage, the bread perfectly browned and the sausage juicy and cooked through. The waitresses sat with him and told him.

His mother had seen something terrible. She had run out of the house, screaming and sobbing. “Something from Hell lives in that house!” she’d shrieked to the first person she came across, a mailman. “Hell lives in that house!”

Calvin’s mom refused to go back in. She refused to say anything about her husband, only that he was not her powerful orator anymore. Darkness had seized him. She would not speak of what had happened, only that her husband was gone.

Calvin had some idea of what had happened. He could see his own father in his mind’s eye, punching the floor until his knuckles were smeared with blood, chanting and coughing until his throat gave out.

He ate his meal. He promised the waitresses he’d come back.

The Kesher family’s house was as stoic and plain as ever. All the curtains were drawn. Calvin opened the front door, and he gagged.

The smell of shit was overwhelming. Calvin kept the front door open. Traffic noise and the dry rustle of summer wind entered the space with him. Darkness rested on everything, made everything alien and strange, and made a family home look like a labyrinth.

Below the wind, below the traffic, Calvin couldn’t hear anything. There was no coughing anymore.

Calvin moved further in the house and listened more. Soon, something new came to his hearing aids: the sound of soft wheezing.

His father’s bedroom door was closed. As Calvin approached, the wheezing seemed to grow and fill the empty space.

Calvin opened the door. He reached in the darkness, towards the wheezing, and felt for the light switch. He turned the light on.

The wheezing stopped. There was a hole in the bedroom floor, a shovel handle sticking out of it. There was a puddle of dark liquid, liquid that must have been blood; there were clumps of dry, dry dirt. There was also a mass of pink muscle, a clear liquid collecting around it. Calvin stared at the mass and found his own hand pressing at his own neck. He swallowed. “Dad?” he called.

A hand shot out of the hole and landed in the puddle of blood. It was caked brown with dirt. There were darker patches of blood on the hand, the fingernails raw and broken. His father’s other hand, just as dirty and bloody, came up and grasped at the edge of the hole.

His father materialized. Blood trickled down his face, came from his mouth, and streamed down his chin; his eyes were wet and shiny with fever. Dirt covered every inch of him. He stared at Calvin, but no recognition entered his eyes.

Calvin’s father, the powerful speaker, was silent and unrecognizable, lost to another world. Los Suelos had lost its head preacher.

The dirty stranger held up a hand. His last three digits touched his thumb while the index finger shot straight up in the air. Next, there was a fist, only the pinkie pointed up in the air. Then the thumb and index finger were pointing away from the palm, parallel to each other.

“Dig,” Calvin’s father fingerspelled, again and again. “Dig.”

Calvin backed away from the doorway. The stranger descended back down into the hole, into the earth.

The bedroom light turned off. Darkness was the house’s only resident now.

Featured image by Ian Kappos.